Cascade

Historical Background

Ancient settlers depended primarily on wetland ecosystems such as flood plains and associated resources. They established and developed their settlements along flood plains and riverine habitats. Most rivers and streams found in the dry zone of Sri Lanka are seasonal, and their flow is dependent on the amount of rainfall received. Irrigation tanks were created by constructing an earth bund or dam across a seasonal or perennial stream. The tank is then filled with water that flows from the stream.

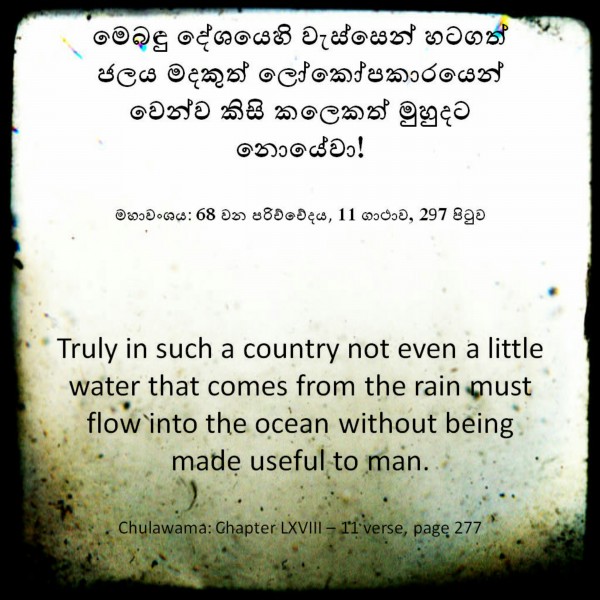

The water collected is stored and used for irrigation, domestic and other needs of the village. The creation of irrigation tanks allowed villages to almost always have a sufficient amount of stored water for use, even when the streams were no longer flowing. The tank cascade system can therefore be described as a ‘human adaptation to rainfall patterns’ (Someratne et al., 2005). This increase in water availability for irrigation made two seasons of annual cultivation possible. Rainwater harvesting reservoirs and tanks were developed in the ancient kingdoms of Anuradhapura (437 BC-845 AD) and Polonnaruwa (846 AD-1302 AD), changing the ecology of the north central dry lowlands.

At present, there are approximately 12,000 ancient small dams and 320 ancient large dams, together with thousands of man-made lakes in Sri Lanka, with over 10,000 reservoirs in the Northern Province alone. The tanks have become naturalized. This means that although these tanks and reservoirs were established by people, over time, they have become integrated with their surroundings and are now a part of the landscape. Tanks and reservoirs support a rich diversity of species and habitats.

Source: Someratne et al. (2005).

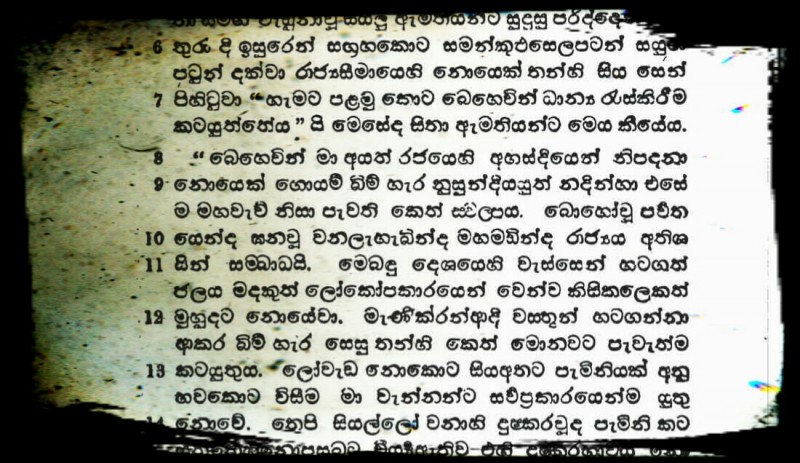

Major ancient irrigation works in Sri Lanka

| King | Period | Records of construction and restoration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| King Pandukabhaya | 437 | – | 367BC | Abhaya Wewa (Basawakkulama Wewa) rainwater reservoir in Anuradhapura |

| King Vasabha | 66 | – | 110AD | Kuda Vilachchiya, Maha Vilachchiya and Elahera Canal. First record of major irrigation work; construction of a dozen irrigation canals and eleven tanks (with the largest having a circumference of 3 km) |

| King Mahasena | 276 | – | 303AD | First giant reservoirs, including the vast Minneriya Tank and fifteen other reservoirs |

| King Dhatusena | 459 | – | 477AD | Kala Wewa (a vast rainwater reservoir) and Jaya Ganga (also called Yoda Ela) — a remarkable 90 km long canal with a subtle gradient of 1 ft per mile (examples include Yakundava Tank, Gomathi Canal and Giant’s Tank) |

| King Moggalana | 495 | – | 512AD | Padaviya Tank (the largest tank at the time). At present, following restoration, it is slightly smaller than Kala Wewa and Minneriya Weva |

| King Aggabodhi II | 608 | – | 618AD | Giritale Tank and several other tanks |

| King Dappula II | 797 | – | 802AD | Pandu Wewa (Pandu water reservoir) |

| King Parakramabahu | 1153 | – | 1186AD | Referred to as ‘King Parakramabahu the Great’ and considered the ‘royal master builder of tanks’. During the reign of this great king, Sri Lanka became to be known as the ‘Granary of the Orient’. King Parakramabahu the Great was responsible for the construction or restoration of 165 dams, 3,910 canals, 163 major tanks and reservoirs, and 2,376 minor tanks, within his reign of 33 years. Thus, he was responsible for many of the supreme developments in irrigation and agriculture that mark the 2,550 year long history of Sri Lankan civilization |

Sources: Fernando (1980); Geiger (1912)